On the history of works of art and cultural objects - Museum Wiesbaden (Part 2)

Bringing true provenance to light is like a criminological hunt for clues. In 2009, the Museum Wiesbaden’s Miriam Olivia Merz began systematically investigating the background of more than a hundred paintings acquired during the National Socialist era. In the case of 20 of them, she was able to eliminate the possibility that they had been seized as a result of persecution from their rightful owners. In the case of four paintings, however, the scientist proved that they were "Nazi-looted art".

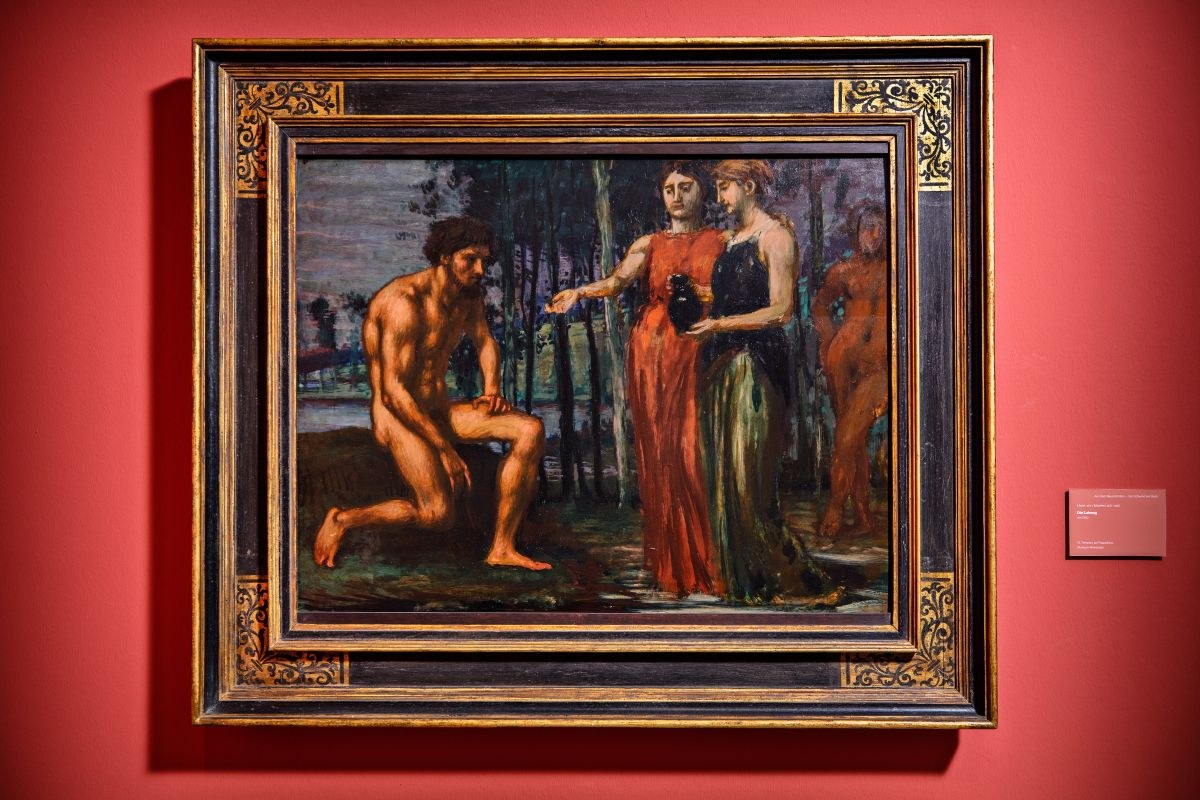

The restitution of the work Die Labung by Hans von Marées demonstrates how to proceed in a solution-oriented manner following such an outcome. The museum submitted the dossier with the results of the research and the recommendation for restitution to the Hessian Ministry for Science and Art for legal examination. Eventually, the work was restituted, i.e. returned, in this case to the descendant of Max Silberberg. The painting’s provenance brings home the fate of German Jews that was as tragic as it was typical: because of his faith, the successful and eminent industrialist from Breslau lost his reputation and job, his possessions and his life in Auschwitz. Miriam Olivia Merz stands before the painting and explains why it is hanging in the collection again today: in April 2014, it was acquired by the heirs for the collection of the Museum Wiesbaden. Merz says, "We are pleased that we were able to clarify the painting’s background and that it can be shown and loaned again as the rightful property of the state". What happens to objects whose background cannot be clarified beyond doubt? "They are published in the 'Lost Art' database in order that potential heirs around the world have the possibility of being able to contact the current owners," Merz explains.

Since January 2015, the art historian has been working for the Central Office for Provenance Research in Hessen, which was newly founded in Wiesbaden at the time. Together with Dr Ulrike Schmiegelt-Rietig, she traces the many varied and often, because of the war years, convoluted ways in which works of art came into Hessian possession. "In this way, we are putting the museums in the position of being able to face up to their responsibility according to the Berlin Declaration," explains Merz in an office filled with bookshelves. She is referring to the joint declaration of the Federal Government, the States and the municipal umbrella organisations to substantially intensify the search for Nazi-looted property in their own inventories. "I have always been fascinated by the history of works of art," Merz explains while looking at an exhibition catalogue from the 1940s, "but we don't create facts ourselves: we provide clarity."

Previous article in the series:On the history of works of art and cultural objects - Museum Wiesbaden (Part 1)

Next article in the series:

On the history of works of art and cultural objects - Museum Wiesbaden (Part 3)

Gallery

Published on 23.03.2018

Share on Twitter?

By clicking on this link you leave the Kultur in Hessen website and will be redirected to the website of Twitter. Please note that personal data will be transmitted in the process.

Further information can be found in our privacy policy.

Share on Facebook?

By clicking on this link you leave the Kultur in Hessen website and will be redirected to the website of Facebook. Please note that personal data will be transmitted in the process.

Further information can be found in our privacy policy.